Bring on the robots and create better jobs, report argues

Canadian businesses are failing to invest adequately in new technology and R&D, hurting productivity and negatively impacting the composition and quality of work, according a new report by the Centre for Future Work.

“Far from losing sleep over whether robots are going to take our jobs, Canadian workers should be more concerned with the slow pace of technology adoption by businesses,” says economist Jim Stanford, director at the Centre for Future Work and author of the report.

“The failure of employers to implement new technologies is causing an over-reliance on low-quality work, holding back our productivity and incomes, and squandering the potential for safer jobs and more leisure time,” he said in an email to Research Money.

Stanford directs the Centre for Future Work, an independent research organization founded in 2016 and housed in the Vancouver headquarters of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. The report, "Where are the Robots?", maintains that public discussion about the future of work has been strongly influenced by widespread fear that accelerating technological change will displace large numbers of workers by robots and other machines.

However, there is no empirical evidence that the introduction of robots and other forms of automated machinery and technology is accelerating in Canada, according to the report. In fact, by several different measures, the development and application of new technology by Canadian businesses is slowing down, not speeding up, the report found.

“The pace of business investment in innovation, technology and machinery is in fact too slow for Canada to fulfill its potential as a global economic leader,” Stanford said.

“Sustained weakness in innovation, M&E [machinery and equipment] investment, capital intensity, and productivity are damning indictments of the failure of Canada’s business sector to fulfil its assigned role as engine of economic dynamism,” he said.

Business investment declining in innovation, R&D, new machinery and technology

The report used nine empirical indicators of Canadian innovation, technology adoption and robotization in the Canadian workplaces, including:

- Slowing Business Investment in Innovation:

In the last two decades, the innovation activity of Canadian businesses has eroded markedly. By 2012, these investments equaled 1.8 per cent of GDP — down one-fifth from a peak of 2.3 per cent of GDP in the early 2000s.

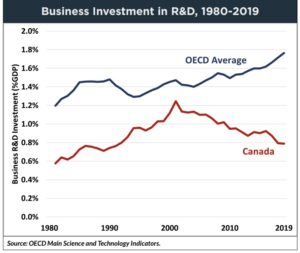

- Canada’s Lagging R&D Effort:

By 2019 (most recent OECD data available), Canadian business R&D spending was less than half the average (as a share of GDP) of other industrial countries.

In that same year, Canada ranked 26th among the 37 industrial countries that belong to the OECD. Canada’s business R&D effort fell by one-third of a percentage point of GDP between 2000 and 2019 — “the third-worst decline in business R&D among all OECD countries,” according to the report.

- Slowing Business Investment in Machinery and Technology:

Business investment in modern machinery and equipment — the most tangible manifestations of new technology — has plunged dramatically, according to the report.

By 2021, this investment equaled three per cent of GDP — “by far the lowest in Canada’s postwar history, and less than half the average recorded over the second half of the twentieth century,” said the report.

The beginning of this long decline in business machinery investment in Canada coincides wit the introduction of major reductions in business taxation at the federal and then provincial levels, noted the report. This resulted in a reduction of over one-third in the combined federal-provincial corporate tax rate.

“This important policy change was predicated on the assumption that lower corporate taxes would inspire companies to invest more in new capital and technology, not less,” said the report.

However, the unprecedented weakness in business capital spending on technology “should motivate a deep rethinking of the rationale and effectiveness of corporate tax cuts as a tool for eliciting business investment,” Stanford said.

- Eroding Capital Stock:

In recent years, the very slow pace of business investment in machinery and equipment (about three per cent of gross investment each year from 2010 to 2015), means that new investment has not been sufficient to offset wear and tear of the existing capital stock. “The result is an unprecedented shrinkage in the net stock of tangible equipment that Canadian workers use to do their jobs,” stated the report.

- The Capital-Labour Ratio is Falling:

The aggregate ratio of capital to labour in the economy has been declining for several years, falling by a cumulative total of about three per cent between 2015 and 2019, according to the report. The report observed a decline in machinery-labour ratio by a cumulative total of more than 11 per cent since 2014.

“In other words," the report concluded, "the typical Canadian worker uses 11 per cent less machinery and equipment to do their job with today, than they did in 2014."

Productivity growth, robotization both slowing

Canada’s labour productivity growth has been slower than that of the top countries for many decades, hurting the country’s international competitiveness, according to the report.

Since 2000, mean productivity growth in Canada’s economy has been the weakest since records began in 1961, averaging 0.8 per cent annually, or less than half the mean rate in the 1960s and 70s.

This is due to several factors, said the report, including “the failure of Canadian businesses to adequately invest in new technologies and ideas, and to put those ideas into practice through investments in tangible machinery and capital.”

As for the fear of robots replacing workers, in 2020 Canada ranked 19th among countries in the intensity of industrial robot use (number of robots per 100,000 manufacturing workers), based on data from the International Federation of Robots.

“Canada’s rate of installation of new robots is slowing, and our ranking in robot use among countries is falling accordingly: down from 12th place in 2015, just five years earlier,” according to the report.

“The problem is not that robots are displacing workers from jobs in large numbers," insisted Stanford. "The bigger problem is that Canada isn’t using enough robots — and using them well, to build high-value global industries."

Government needs to provide targeted incentives, technology procurement

The report makes six policy recommendations to improve innovation and technology adoption in Canada.

Rather than across-the-board corporate tax cuts, governments should provide businesses with incentives — such as accelerated depreciation for capital investment or investment tax credits — contingent on new investments being made in machinery and technology, Stanford said.

Public sector and public services agencies need to become leaders in the adoption and application of new technology, which would help maximize public sector productivity, he added.

Procurement purchases by Canadian public sector organizations, focused on machinery and technology purchases with stronger Canadian content, would help nurture home-grown innovation with initial home-market sales, he added.

For Stanford, the worst thing governments could do, in terms of encouraging businesses to invest in labour-saving technology, is to “help” employers find alternative sources of cheap, compliant labour. This short-circuits the natural consequences of tighter labour markets, which should lead to more thoughtful use of labour, including applying it more productively and finding new technologies to optimize the value-added potential of scarce labour.

“The federal government’s decision to ramp up temporary foreign migrant workers, to respond to complaints of ‘labour shortage’ by employers — mostly in lower-productivity sectors of the economy, such as hospitality and agriculture — is exactly the wrong thing to do if we care about accelerating productivity growth and innovation in Canada,” Stanford concluded.

R$

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.