Editorial: Soylent Green is policy

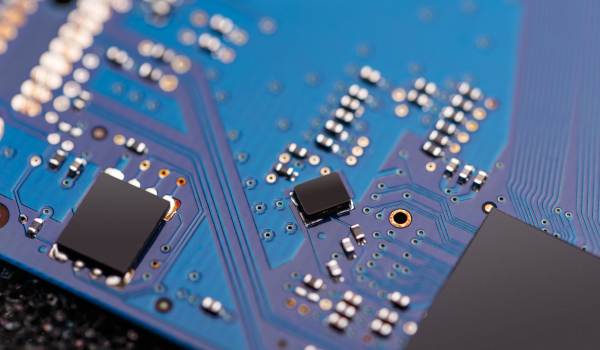

Farms and farmers are not what they used to be. As we worry about policies addressing supply chains for rare earths and semiconductors, we should spare some thought for policy that determines the fundamental structure of Canadian food production.

Other stories mentioning these organizations, people and topics

| Organizations: | |

| People: | |

| Topics: |

Other News

Events For Leaders in

Science, Tech, Innovation, and Policy

Discuss and learn from those in the know at our virtual and in-person events.

See Upcoming Events

You have 0 free articles remaining.

Don't miss out - start your free trial today.

Start your FREE trial Already a member? Log in

By using this website, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies to provide you with a great experience and to help our website run effectively in accordance with our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.